By Nina Sankovitch

Reviewed by Heather Cameron

Nina Sankovitch’s beloved oldest sister, Anne-Marie, died four months after her initial cancer diagnosis. She was 46. The author filled the years after her sister’s death with relentless activity. She felt compelled to justify her continuing existence. “My sister had died, and I was alive. Why was I given the life card, and what was I supposed to do with it?”

Three years later, as she approached her own 46th birthday, Sankovitch was still consumed with grief. She needed to find another way to come to terms with her loss. She realized that the more she thought about how to get herself back together as one sane, whole person, the more she thought about books. She and her sister had grown up in a home filled with books. The love of reading was instilled at an early age. As adults, the two sisters enjoyed recommending books to each other, reading them and discussing them. This shared interest created a strong bond and was an immense comfort to both of them during the last four months of Anne-Marie’s life.

“For years,” Sankovitch writes, “books had offered to me a window into how other people deal with life, its sorrows and joys and monotonies and frustrations. I would look there again for empathy, guidance, fellowship, and experience. Books would give me all that, and more. After three years of carrying the truth of my sister’s death around with me, I knew I would never be relieved of my sorrow. I was not hoping for relief. I was hoping for answers. I was trusting in books to answer the relentless question of why I deserved to live. And of how I should live.”

She set herself the challenge of reading a book a day for a year. She established some ground rules – she would not read any author more than once, not reread books previously read, and she would write about each book she read. All the books she would select would be ones she and Anne Marie would have “talked about, argued over, and some we would have agreed upon.” Her year of reading would be her “escape back into life.”

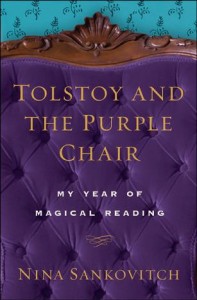

She set up an “office” in a little room in the family home that she shared with her four school-aged boys and husband. She set up a few book cases and reclaimed a battered old arm chair, stained from years of use, and a little smelly, thanks to the family’s incontinent cat. This was the purple chair in which she did most of her reading that year.

Sankovitch roamed far and wide in her year of magical reading. She read classics, contemporary literary fiction, biography, philosophy, memoir, historical fiction, mysteries, detective stories, works of philosophy and narrative non-fiction. (There is a complete bibliography in the book.) However, Tolstoy and the Purple Chair is not primarily the story of her experience reading a book a day (the occasional fatigue, the frequent joy, the scheduling challenges, etc.) nor does it simply review the particular books she read. It is primarily about the memories triggered by the characters and themes of the books she reads.

She begins to understand and respect the importance of remembering, and that the only “balm to sorrow is memory; the only salve for the pain of losing someone to death is acknowledging the life that existed before.” She realizes that she had been “facing the wrong way and looking at the end of my sister’s life and not at the duration of it.” Reading the stories of others, both fictional and actual, remind her that “suffering and finding joy are universal experiences” that connect people. She sees how important it is to find the beauty in a person or a situation and to hold onto it for a lifetime.

Tolstoy and the Purple Chair is a wise and moving book, one that would have made a worthy addition to works Sankovitch read in her remarkable and productive year of magical reading.